Last week, the International Court of Justice heard three days of argument concerning Timor-Leste’s pending request for provisional measures in Questions relating to the Seizure and Detention of Certain Documents and Data (Timor-Leste v. Australia). The case was brought by Timor-Leste following Australia’s execution of a search warrant at the office of Timor-Leste’s Canberra-based attorney. Australia claimed that the warrant was appropriately issued for national security purposes, and used it to obtain extensive electronic and paper files concerning Timor-Leste’s pending arbitration against Australia before a Hague tribunal. In that arbitration, Timor-Leste is seeking to overturn a 2007 treaty between Australia and Timor-Leste, as a result of Australia’s espionage on Timor-Leste’s internal communications during the course of negotiations.

Australia claims that it was justified in seizing Timor-Leste’s legal files because Timor-Leste’s evidence of Australia’s espionage was provided by a retired Australian spy. That spy, dubbed “Officer X,” informed Timor-Leste of the 2004 bugging operation as a result of his belief that the surveillance had been conducted for improper commercial purposes, rather than national security interests.

It is a complicated and messy situation, both legally and politically, but the significance of Australia’s seizure of Timor-Leste’s legal files, as well as Australia’s prior espionage against Timor-Leste’s government, can only be understood in the context of the history of the past treaty negotiations between the two countries. To give some background for future posts concerning the legal claims being raised by Timor-Leste and Australia, provided here is a timeline of events leading up to the recent case before the ICJ.

The International Legal Context

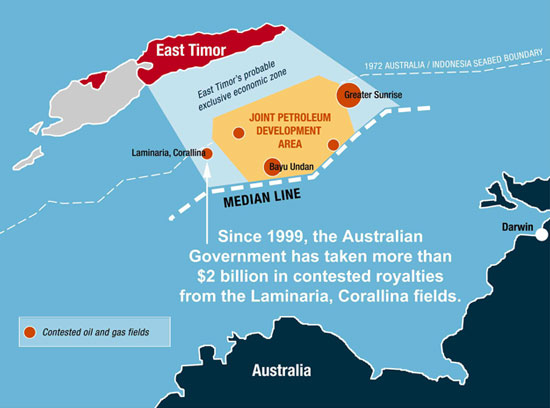

The dispute ultimately concerns Australia and Timor-Leste’s competing claims to an expansive section of the Timor Sea between Australia and Timor-Leste. If you drew a line in the middle of the ocean that was equidistant from both Timor-Leste and Australia’s shores, the maritime area stretches north from that median line to within approximately 40 nautical miles of Timor-Leste’s shore. There is a lot of oil and gas in this area of the ocean, and both Australia and Timor-Leste claims to have the sovereign right to exploit those resources.

Australia claims that this area belong to Australia on the basis of historical precedence and on the basis of somewhat dubious allegations concerning the underwater geographical features of the Timor Sea. Timor-Leste claims that it belongs to Timor-Leste on the basis of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the widely prevalent state practice of delimiting maritime boundaries of states with opposite coasts along a median line. Timor-Leste’s claims are generally considered more robust than Australia’s.

Although the strength of Australia’s legal claims to the territory may be questionable, it turns out that inconvenient little problem becomes entirely irrelevant if a legal challenge is never actually brought. Australia almost certainly recognizes that it will not be able to prevail in acquiring the territory for itself, and so rather than pursuing its own claims, it has instead strategically eliminated any opportunity for a legal challenge to be brought by Timor-Leste.

Two months before Timor-Leste became an independent nation that was capable of pursuing a claim before an international adjudicative body, Australia withdrew any dispute over maritime boundaries from the jurisdiction of the ICJ and ITLOS, preventing Timor-Leste from ever having had an opportunity to establish its legal claim to the Timor Sea. In the absence of a decision from the ICJ or ITLOS recognizing the likely legal reality of Timor-Leste’s claims to the disputed oil and gas fields, the territory will remain perpetually “disputed.” So long as there is legal limbo over the territory, Timor-Leste is unable to obtain the foreign investment necessary to develop the resources. Australia, in turn, can continue to demand that in exchange for allowing foreign investment into the maritime areas, Australia gets a substantial portion of any resulting revenues.

The Disputed Territories

Image from dollarsandsense.org, “Minding The Timor Gap: Billions of dollars in oil and gas revenues are at stake as Australia continues to bully East Timor out of its undersea energy resources.”

Joint Petroleum Development Area (“JPDA”): Area marked in yellow on map. Revenues derived from oil and gas fields in this area are split 90/10 between Timor-Leste and Australia, pursuant to 2002 treaty. Although the JPDA is the largest delineated area within the disputed maritime areas, its gas and oil fields are not as valuable as that of the non-JPDA areas.

Laminaria-Corallina Fields: Located in the western (left) horn of the light blue area. (Light blue area marks maritime territory that is disputed by Australia and Timor-Leste.) These fields have never been a part of any treaty between Timor-Leste and Australia, and Australia has at all times obtained 100% of government proceeds from them. The Laminaria-Corallina fields have now been 95% depleted of their resources, and, as a result, no longer plays a significant role in the dispute between Australia and Timor-Leste.

Greater Sunrise Fields: Located in the eastern (right) horn of the light blue area. (Light blue area marks maritime territory that is disputed by Australia and Timor-Leste.) The Greater Sunrise fields are estimate to contain twice as much LNG as the JPDA fields. A small portion of the Greater Sunrise fields (20%) is located in the JPDA, but most of the fields’ area (80%) lays outside of it, in the disputed territory over which both Australia and Timor-Leste. Under the 2002 treaty between Timor-Leste and Australia, Timor-Leste received 90% of the revenue from the sliver of the Greater Sunrise fields in the JPDA, and 0% of the revenue from the Greater Sunrise fields outside of it. (Or, 18% of the revenue from the Greater Sunrise fields as a whole.) Under the 2007 treaty, Timor-Leste and Australia each receive 50% of future revenues from the entirety of the Greater Sunrise Fields. As of 2014, the Greater Sunrise fields have yet to be commercially developed.

Timeline of Events

August 1974: Woodside Australian Energy (later Woodside Petroleum), an Australian energy company, discovers gas in the Greater Sunrise fields.

1975: Indonesia invades and annexes East Timor, making further development of the Timor Sea resources impossible.

1989 – 1991: Indonesia and Australia sign and ratify the Timor Gap Treaty (“TGT”), opening the possibility once again of exploration and development of the Timor Sea gas and oil fields. The Timor Gap Treaty does not establish maritime boundaries between the countries but instead equally splits proceeds derived from development of the oil and gas fields in a delineated portion of the Timor Sea between the countries, with each country receiving 50% of the total tax revenues. Many observers believe that this 50%/50% division is not supported by international law, but was instead agreed to by Indonesia as a concession in exchange for Australia’s recognition of its annexation of Timor-Leste.

1995: Australia, pursuant to the Petroleum (Submerged Lands) Act of 1967, its sovereign claim to the resources of its continental shelf, and the TGT, issues licenses to a joint venture between Woodside and Shell for exploration and drilling of the portions of the Greater Sunrise fields that lie outside of what will later become the JPDA. The largest portion is within permit area NT/RL2, with an additional small portion in NT/P55.

1997: The Woodside and Shell JV announce proposals to set up a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant in Darwin, Northern Territory, with production scheduled to commence in 2005.

August 1999: East Timor votes for independence, potentially throwing long-term development plans in the Timor Sea into doubt, due to uncertainty over future treaties and boundary determinations.

1999: Three multinational corporations, headed by Woodside, begin oil production in the Laminaria-Corallina fields. Between 1999 and 2012, approximately 201 million barrels of oil are produced, with resulting tax revenues to Australia of approximately $2 billion USD.

February 2001: Woodside, Shell, and Phillips Petroleum Company sign a cooperative agreement, establishing a joint venture for development of both the Bayu-Undan fields (within the JPDA) and the Greater Sunrise fields (in both JPDA and outside of it). The consortium companies base their agreement on a belief that the majority of the Greater Sunrise fields are “located in Australian waters.”

July 2001: Timor-Leste, in advance of its independence from Indonesia, had made it clear that Timor-Leste would not be bound by treaties previously entered into by Indonesia, including the Timor Gap Treaty, which concerned the soon-to-be new nation’s claimed territories. As a result of historical factors, both Australia and East Territory lay claim to large, resource-rich maritime area in the Timor Sea, and the nations are unable to reach an agreement as to their respective maritime territorial boundaries. Australia and Timor-Leste instead reach a Memorandum of Understanding of Timor Sea Arrangement (MOU) (which will later be adapted into the Timor Sea Treaty) under which proceeds from development in the JPDA, will no longer be split 50/50, but will instead be split 90/10, with 90% going to Timor and 10% going to Australia. This agreement does not, however, address the proceeds from resources obtained in disputed territories outside of the JPDA area, and Australia continues to receive 100% of government revenues from the resources in these areas. The MOU also specifies that the Greater Sunrise fields are to be divided with 80% going to Australia and 20% going to East Timor, based upon Australia’s claim to the waters outside the JPDA.

The MOU also specifically preserves the Woodside/Shell/Phillips joint venture’s contracts to the portion of the Greater Sunrise fields located in the JPDA.

Early March 2002: Oceanic Exploration Company, an oil and gas exploration company interested in developing the Timor Sea oil and gas fields, ”offer[s] to finance a claim by East Timor in the International Court of Justice to support East Timor’s expanded seabed boundary claims in its dispute with Australia and to establish expanded boundaries for East Timor. Such expanded seabed boundaries, under applicable international law, would have tripled East Timor’s seabed hydrocarbon reserves.”

March 21 and 25, 2002: Australia files reservations with both the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), revoking Australia’s consent to jurisdiction before those tribunals for any disputes involving maritime boundaries. The apparent purpose is to prevent any claims arising from the Timor Sea dispute from being heard by either the ICJ or ITLOS, in anticipation of Timor-Leste’s rapidly approaching independence.

May 20, 2002: Timor-Leste gains independence from Indonesia. On the same day, Australia and Timor-Leste enter into the Timor Sea Treaty (“TST”) as an interim agreement to replace the Timor Gap Treaty (which went out of force with Timor-Leste’s independence). The TST continues the 90/10 split agreed to in the 2001 provisional agreement, and provides for a stopgap treaty concerning the division of the resources in the Timor Sea.

2002 – 2004: Timor-Leste and Australia engage in negotiations over the disputed territories outside of the JDPA area, but negotiations are unsuccessful. This is due in large part because Timor-Leste wants to establish its maritime territorial boundaries over this area, but under the provisions for maritime delineation in UNCLOS, Australia’s claims to the resources in the Timor Sea could be largely be extinguished. The two major oil and gas fields outside the JDPA are each subject to different pressures:

- Laminaria-Corallina Fields: Australia is at this time obtaining revenues from the Laminaria-Corallina fields in the amount of approximately $1 million per a day, and every day that passed without a treaty meant more revenues that Australia can claim entirely for itself. In contrast, every day that passed for Timor-Leste was another day in which it got no share of the revenues from the rapidly depleting fields, and would forever lose that source of revenue.

- Greater Sunrise Fields: In 2003, a multinational consortium, in which Woodside was once again the majority partner, obtained a license to development the resources contained in the Greater Sunrise Field. Due to the legal uncertainty caused by Timor-Leste and Australia’s disputing claims to the territory in which it was located, however, Woodside refused to fully invest in the fields until a firm agreement was established. For Australia, developing the Greater Sunrise fields would have been a good revenue source, but not if it came at the cost of its claims to the rest of the Timor Sea – which made Australia reluctant to open negotiations at all. For Timor-Leste, the revenues from the Greater Sunrise fields were urgently needed, but it lacked the resources to develop these fields on its own. Unless Australia would agree to resolve the territorial dispute, Timor-Leste could not obtain the outside investment required to obtain the resources.

As a result of the investors’ demands and Timor-Leste’s inability to proceed alone, Australia could effectively hold the Timor Sea territories hostage. By preventing any adjudication over Timor-Leste’s claims, Australia could prevent Timor-Leste from benefiting from the resources it was likely entitled to under international law, as well as continue to receive all revenues from the existing gas and oil production. Although Timor-Leste wanted to develop the remaining gas and oil fields (as well as lay claim to the existing revenue sources that Australia continued to receive), Timor-Leste lacked the infrastructure or financing to do so without foreign investment – and foreign investors refused to invest while Timor-Leste and Australia had disputing claims to the territory.

Australia could afford to be patient. As long as no action was taken, Australia would to continue obtaining 100% of the revenue from the existing fields, which had been developed prior to Timor-Leste’s independence and therefore before any legal dispute arose. Australia had no urgent need for the potential revenue that could be obtained from the other oil fields, especially when it was unclear that Australia would be entitled to any of that revenue at all – and when Timor-Leste was so desperate for that revenue that Australia could simply wait Timor-Leste out, and force it to voluntarily agree to give up is territorial rights in exchange for Australia allowing development to occur at all.

Consequently, during the 2002 to 2004 time period, negotiations are slow. Australia announces that it would wait 20 years to resolve the question if it had to, while Timor-Leste continued to petition Australia for a final agreement as to the boundaries. But this stalemate is eventually broken, thanks to the third party involved in the Timor-Leste/Australia treaty negotiations: the Woodside-led consortium, which was tired of delays, and waiting impatiently to develop the Greater Sunrise fields.

In 2003, Australia and Timor-Leste sign the Sunrise International Unitization Agreement (Sunrise IUA), but Timor-Leste’s parliament, believing it to be a bad deal, refuses to ratify it.

July 29, 2004: Woodside’s executive director personally flies to Timor-Leste to inform Timor-Leste’s prime minister that, if a treaty could not be reached by the end of the year, Woodside would terminate its operations in the Greater Sunrise fields and pull out its investment all together. At the same time, Woodside informed Australia of its strong interest in a quick resolution to the dispute over the Greater Sunrise fields. Following this political pressure, Australia and Timor-Leste begin considering a ‘creative solution’ to the problem, under which the question of territorial boundaries would be pushed off, and an agreement concerning resources would be reached.

September 20, 2004: Timor-Leste and Australia meet in Dili, Timor-Leste’s capital, to start a new round of negotiations concerning a treaty for the development of the Greater Sunrise fields.

October 2004: During the course of negotiations in Dili,

- Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer allegedly orders the eavesdropping of the Timor-Leste’s parliament’s discussions concerning treaty negotiations. The listening devices are to be planted by the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (“ASIS”), then headed by David Irvine.

- ASIS agents, posing as contractors for an Australian construction company, install recording devices in the offices of Timor-Leste’s cabinet and prime minister, allowing Australia to eavesdrop on Timor-Leste’s internal discussions concerning treaty negotiations. Australia is likely able to obtain detailed information on Timor-Leste’s planned negotiation strategies and the vulnerabilities it would face if talks fell through. Possible (and very hypothetical) scenarios that could provide particularly strong support for Timor-Leste’s current claim to overturn CMATS might include Australia learning through surveillance (1) that Timor-Leste did not believe Woodside’s bluff that it would pull out, but that if Woodside went through with it, it would have to capitulate; (2) that East Timor had other possible avenues to development it could use as an alternative, which Australia took steps to remove once it learned of it; or (3) information concerning the pending bribery claims in a U.S. federal court, accusing ConocoPhillips (the company with the second largest share, after Woodside, in the Greater Sunrise Joint Venture) of bribing Timor-Leste’s Prime Minister to obtain development contracts for oil fields located in the JPDA.

- The negotiations begin to break down when Australia makes it clear it will not agree to any discussions about the disputed maritime boundaries, and that the only concession Australia was willing to negotiate about was a monetary one. Australia would provide financial compensation to Timor-Leste, and would allow Woodside to proceed with development of the Greater Sunrise fields, if Timor-Leste would agree to forfeit any ability to attempt to establish the maritime boundary through any other mechanism. Timor-Leste was willing to agree to defer on claims to its territorial boundaries, but wanted to participate in the development of the gas and oil fields – a request Australia refused to consider. Australia would agree to give Timor-Leste a portion of the revenues as a pay out, but it would not have any role in the actual development and production of the gas and oil extracted.

November 17, 2004: Woodside’s deadline passes, with Australia and Timor-Leste having failed to come to an agreement to a permanent treaty. Woodside pulls out of its operations in the Greater Sunrise fields, stating that the uncertainty caused by the lack of an established legal framework for the area makes long-term investment untenable.

March-April 2005: Timor-Leste and Australia resume negotiations, this time in Canberra.

April 29, 2005: After three days of talks in Dili, Australia and Timor-Leste reach a draft agreement on development of the Greater Sunrise fields, the terms of which are finalized in the Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (“CMATS”). The CMATS is a great deal for Australia; it makes no concessions to Timor-Leste beyond a strictly monetary 50/50 division of revenues between Australia and Timor-Leste from the Greater Sunrise fields.

It is not a particularly good deal for Timor-Leste. The deal concerns only the Greater Sunrise fields, and not any of the other maritime areas which are in dispute. All areas not within the Greater Sunrise fields or the JDPA remain unaddressed. Financially, Timor-Leste now secures a right to 50% of the Greater Sunrise revenues, when previously Australia had only agreed not to contest Timor-Leste’s right to 18%. But obtaining 50% of revenues is not necessarily an achievement, when there is a good chance a court would have awarded you 100%.

And, perhaps worst of all, CMATS contains a severe ‘moratorium,’ pursuant to which Timor-Leste effectively agrees not to try and establish its territorial boundaries. Article 4 provides that:

1. Neither Australia nor Timor-Leste shall assert, pursue or further by any means in relation to the other Party its claims to sovereign rights and jurisdiction and maritime boundaries for the period of this Treaty.

2. Paragraph 1 of this Article does not prevent a Party from continuing activities (including the regulation and authorisation of existing and new activities) in areas in which its domestic legislation on 19 May 2002 authorised the granting of permission for conducting activities in relation to petroleum or other resources of the seabed and subsoil.

3. Notwithstanding paragraph 2 of this Article, the JPDA will continue to be governed by the terms of the Timor Sea Treaty and associated instruments.

4. Notwithstanding any other bilateral or multilateral agreement binding on the Parties, or any declaration made by either Party pursuant to any such agreement, neither Party shall commence or pursue any proceedings against the other Party before any court, tribunal or other dispute settlement mechanism that would raise or result in, either directly or indirectly, issues or findings of relevance to maritime boundaries or delimitation in the Timor Sea.

5. Any court, tribunal or other dispute settlement body hearing proceedings involving the Parties shall not consider, make comment on, nor make findings that would raise or result in, either directly or indirectly, issues or findings of relevance to maritime boundaries or delimitation in the Timor Sea. Any such comment or finding shall be of no effect, and shall not be relied upon, or cited, by the Parties at any time.

6. Neither Party shall raise or pursue in any international organisation matters that are, directly or indirectly, relevant to maritime boundaries or delimitation in the Timor Sea.

7. The Parties shall not be under an obligation to negotiate permanent maritime boundaries for the period of this Treaty.

Essentially, through CMATS, Australia has solidified its ability to hold the disputed territory hostage for 50 years – because under CMATS, Timor-Leste cannot pursue any legal claim which could, even “indirectly,” legally establish its claims to the Timor Sea. Moreover, if a court does go ahead and make a ruling on Timor-Leste’s territorial boundaries anyway, Timor-Leste is prohibited from even mentioning the court ruling. And by the time those 50 years expire, there won’t be much oil left for the parties to argue over.

Australia, for its part, did very well in obtaining such an expansive prohibition. The fact that Australia’s claims in the Timor Sea are likely wrongful and in violation of international law was effectively rendered irrelevant as a result of the treaty, and Australia’s ability to develop any areas outside of the JDPA or Greater Sunrise fields was left unaffected.

January 12, 2006: Australia and Timor formally sign CMATS, which comes into force in 2007.

January 2008: Alexander Downer retires from politics and establishes a boutique lobbying firm, Bespoke Approach. Woodside becomes a client of Bespoke Approach, and through his lobbying firm, Downer ends up on the payroll of Woodside.

2008 – 2012: Development on the Greater Sunrise fields does not proceed, in large part due to disputes between Woodside, Australia, and Timor-Leste as to how and where the extracted oil will be diverted for processing. At an unknown date in this time period, a retired ASIS Agent, dubbed “Officer X,” who had been in charge of carrying out the 2004 surveillance operation against the Timor-Leste cabinet, contacts Timor-Leste’s government to inform them of the surveillance. Officer X stated that he “decided to blow the whistle when he learned that in his life after politics, Alexander Downer had become an advisor to Woodside Petroleum through his lobbying firm, Bespoke Approach.” He provides Timor-Leste with an affidavit “refer[ring] to the 2004 bugging operation as ‘immoral’ and ‘wrong’ because it served not the national interest, but the commercial interest of big oil and gas.”

December 2012: Timor-Leste sends a diplomatic note to then-PM Julia Gillard, informing her of the espionage that was conducted during the 2004 negotiations, requesting that Australia reopen discussions with Timor-Leste about CMATS. Australia ignores the request.

April 2013: Timor-Leste initiates arbitration proceedings against Australia under the 2002 TST, seeking a declaration that the CMATS agreement is voided due to Australia’s failure to negotiate in good faith by conducting espionage on Timor-Leste’s internal treaty discussions.

May 3, 2013: Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Bob Carr announces in a press release that Timor-Leste has initiated arbitration concerning the validity of CMATS, and that “Timor-Leste argues that CMATS is invalid because it alleges Australia did not conduct the CMATS negotiations in 2004 in good faith by engaging in espionage.”

Late November 2013: As part of pre-hearing arbitration procedures, Timor-Leste and Australia meet to discuss preliminary procedural issues and to exchange information. Timor-Leste provides Australia with a list of witnesses that it intends to call at the upcoming arbitration hearing, including the name of Officer X, as well as tree other “whistleblowers” who are prepared to testify to Australia’s espionage.

December 2, 2013: David Irvine, the former head of ASIS and the current Director-General of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (“ASIO”), Australia’s internal intelligence agency, requests the issuance of a warrant to search to conduct a search of Timor-Leste’s Australian attorney, whose office is located in Canberra. The Australian Attorney General, George Brandis, approves the request, and a warrant is issued under section 25 of the ASIO Act, “for the purpose of collecting intelligence on a matter affecting the security of Australia, concerning possible espionage.”

December 3, 2013: The ASIO carries out the search warrant, seizing materials and documents from the office of Timor-Leste’s attorney. Although Timor-Leste’s attorney has already left for the Hague in preparation for the upcoming arbitration hearing, “[o]ne of Mr. Collaery’s legal assistants, Ms Preston, was alone in the office at the time. The officers presented the warrant authorizing the entry and seizure of documents, but never told Ms Preston what exactly they were seeking, or why. In the pressure of the moment Ms Preston sought to read the warrant but felt so intimidated by the presence of over a dozen ASIO personnel that she could not finish it. Moreover, many of the words in it were blacked out. Her request for a copy was refused on the grounds that it was a matter of national security.”

Additionally, ASIO officers also go to the house of Officer X, where he is interrogated for several hours, and has his passport cancelled. All of this occurs a mere two days before a scheduled hearing before the Hague tribunal, on December 5, 2013, at which the parties were to determine how the whistleblower witnesses would be handled. Australia has denied that preventing Officer X’s appearance at the Hague played a role in the timing of its actions, but has conceded it does intend to prevent his testimony from being introduced.

December 18, 2013: Timor-Leste institutes proceedings against Australia before the ICJ, in Questions relating to the Seizure and Detention of Certain Documents and Data (Timor-Leste v. Australia). Timor-Leste also files a request for a provisional (and expedited) order from the Court instructing Australia to return the seized materials while a final decision on the merits is pending.

-Susan